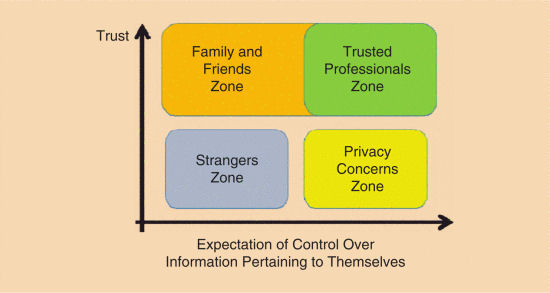

Figure 1. Privacy concerns arise for individuals when there is a high expectation of control over information pertaining to them (CIPT) and low trust.

What if privacy were to disappear completely? Due to the vast information-sharing capabilities of the Internet, privacy is being steadily eroded and redefined. Despite much effort to the contrary, many experts believe privacy is either dead or dying.

A decade and a half ago, Sun Microsystems CEO Scott McNealy declared “you have zero privacy anyway. Get over it” [1]. More recently, Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg stated that sharing is the current social norm, which has replaced privacy [2]. Even more recently, revelations about U.S. NSA’s eavesdropping on U.S. citizens and on foreign heads of state have painted a bleak picture of the current state of privacy.

Despite their claims that privacy is still important, almost half of U.S. citizens say they would be willing to sacrifice privacy for improved tools for shopping, and 30 percent were also willing to forego some privacy for online gaming, social networking, and banking.

If privacy becomes extinct, what options and implications will exist for humanity?

Some argue that because privacy should be a right, people are unwilling to pay for it [3]. Even when considering a trade-off between privacy and some benefit, people seem to have a clear picture of the immediate benefit, but they have a fuzzier perspective on the privacy implications of their data (e.g., data shared with third parties, likelihood of data breaches). Privacy is further eroded when almost any software product requires users to summarily accept lengthy Terms and Conditions documents that are difficult to read and interpret, and that give companies great latitude in collecting and using user data.

In this article, rather than proclaiming the impending “death of privacy” [4] or proposing ways to keep privacy alive, we ask a “what if?” question: If privacy becomes extinct, what options and implications will exist for humanity?

Privacy Defined

Alan Westin defined privacy as “the claim of individuals, groups, or institutions to determine for themselves when, how, and to what extent information about them is communicated to others” [5]. Federal regulations define private information as “information about behavior that occurs in a context in which an individual can reasonably assume that no observation or recording is taking place, and information which has been provided for specific purposes by an individual and which he or she can reasonably expect will not be made public (for example, a school record).”

Privacy concerns arise when two conditions are met. First, people expect to have some level of control over information pertaining to them (CIPT): they expect to be able to control or limit such information. Second, people also have a lack of trust or concerns that other parties might access the information (yellow area in Fig. 1). Of course, in the context of many interactions (both online and in the physical environment) users might not even be aware of privacy issues. Users might leave digital breadcrumbs via cookies and on surveillance cameras without ever considering privacy. In such situations, users should have, but do not have, privacy concerns.

There are two other zones in Fig. 1. The low trust, low expectation of the information control zone (blue area) concerns the inconsequential information people exchange with strangers. The family and friends zone (orange area) is characterized by high trust and low expectations of CIPT, although some family interactions involve high expectations of CIPT.

In general, the expectation of CIPT is a matter of degree: information may be already publicly available, but the information owner might prefer to keep it from becoming more available than it already is. For example, there is considerable concern about the privacy implications of making databases of public paper records available online, as this can greatly facilitate the ability of third parties to search and mine public records [6]. Similarly, even when children are playing in a public place, many parents would object to strangers video-recording the children. Two people on a bench in a public park expect to have a private conversation even though they are in a public space. An expectation of CIPT exists when a) information is not publicly available; b) it is publicly available, but not readily available (e.g., in paper-based files, but not online); or c) it is publicly available but only fleetingly and is not intended to be recorded (for example a conversation in a public place). Although expectations such as b) and c) may be warranted for now, technology evolution could make those expectations irrelevant in the future: thanks to online dissemination, any information that is publicly available even briefly or in a limited location might become widely available in space and time.

Lack of trust is also a critical issue related to CIPT. Highly private information is routinely shared with parties that are both trusted and that have a need to know the information: doctors, lawyers, and tax preparers (“trusted professionals’ zone,” green in Fig. 1). Both culturally and legally, these trusted professionals are obligated to maintain the confidentiality of the information with which they are entrusted. While privacy is a loosely defined right, confidentiality is formally defined in law.

Before Privacy

Privacy is a relatively recent concept. For most of humanity’s history privacy was not a major concern for three primary reasons: lack of an expectation of CIPT, high trust, and lack of information inequalities. People lacked an expectation of privacy because communities had more pressing needs and a culture of sharing. Before the industrial revolution, other issues loomed larger than privacy in Maslow’s hierarchy of needs [7]. Physical security, availability of basic necessities, basic liberties (freedom from slavery, freedom of religion, etc.) were often in short supply and more pressing needs than privacy. Just the opposite of privacy, individuals tried to stay close to other members of the community to minimize the risks of both human and environmental dangers. Banishment from a community was often a death sentence rather than an opportunity to enjoy privacy. Even today, while privacy is not ignored in developing countries, it does not rise to the level of other more immediate concerns: poverty, lack of access to clean water, or lack of personal safety.

The second reason privacy was not a major concern related to a lack of informational inequalities. In small communities, all members have essentially equal access to information about all other members. This mutual knowledge led to mutual trust and was a critical glue that kept the community together, for example by ensuring equity in sharing resources and by policing inappropriate behaviors. Having something to hide would raise suspicions, rather than provide privacy. In contrast, privacy concerns today are primarily with powerful entities that collect private data, for example governments spying on citizens or corporations tracking customers.

The Birth of Privacy

As communities grew, the expectation of privacy arose partly because it is easier to be anonymous in a crowd. Particularly in larger communities with increasing mobility, people developed a higher expectation of CIPT, just as they lost trust in their fellow citizens. Unlike in a small group, it is more difficult or impossible to acquire information about everybody in a large community. The expectation of CIPT increases as the individual expects that the larger community will be unable to get information about him or her, just as the individual knows less about most of the others in the larger community. At the same time, trust in others typically decreases, partly due to reduced familiarity with most other community members. Trust is typically built over time, in repeated positive and mutually reinforcing interactions with the same people or groups of people. Because such long-term interactions are not possible with the majority of the members of a large community, trust is either decreased, or developed with only a small subset of the community members. In contrast, trust can develop more easily in smaller communities, where by necessity or as a result of simple probability law the interactions will tend to be repeated within the entire group of individuals. This new pattern of information flow in larger communities affects both aspects of privacy (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. As smaller communities evolved into larger communities, people’s expectation of control over information pertaining to themselves increased and their trust in others decreased, creating a need for privacy.

Modern life requires people to interact with big entities, and all these interactions require us to relinquish private information to entities we might not trust.

A third reason that trust is reduced in large communities is the rise of larger and relatively more powerful entities (governments, corporations), which lead to further increases in information inequalities. Moreover, modern life requires people to interact with big entities: we need to pay taxes, open bank accounts, fly to meet business partners, and all these interactions require us to relinquish private information to entities we might not trust. Although some regions (e.g., the European Union) have stricter laws on what corporations and governments can do with data they collect (e.g., limits on selling data to third parties), the challenge of balancing data collection with privacy is a worldwide concern, as people resent the data collection itself. Finally, another reason for the increased relevance of privacy is that, as society evolved, more fundamental needs of the individuals (food, shelter, safety) were more readily met, bringing privacy to the forefront, as a relevant human need.

As an illustration, for the historical reasons mentioned above, privacy is not explicitly mentioned in the U.S. Constitution. Although protections exist against unwarranted searches and against the use of one’s home to house troops, there is no mention about safeguarding private information. Not only were today’s telecommunications technologies not anticipated, but historically communities were close knit and based on trust and information sharing, which is probably why privacy was not more of a concern. Only by the beginning of the 20th century did privacy start being mentioned in legal documents, often in response to technology-based challenges and assaults. Jarvis [8, pp. 65–73] presents a detailed history of the beginning of privacy, even chronicling when the word first appeared in Western European languages, and what its initial meanings were.

The Death of Privacy

The erosion of privacy is further exacerbated by the many information aggregators who are engaged in deliberate collection and dissemination of information.

Advances in telecommunications technologies have led to easier information sharing, most recently due to the advent of the Internet and social media. Privacy experts warn that anything posted on the Internet is likely to remain available for an indefinite length of time. Once published, information cannot be made private again. Although any one Internet page may be alternately available and unavailable, frequent copying of content, sharing, and caching may result in information surviving long past the original poster’s intentions. Moreover, information about any one individual may be posted by others, with or without malicious intent, and with or without the individual’s knowledge. For example, photos of an individual in a private setting may be posted by friends, with or without the individual’s knowledge. Strangers might record an individual in a public setting unintentionally, as they record the setting for their own legal and common-sense purposes. Many authors compare the current state of privacy with the vision of the Panopticon. a type of prison conceived by British philosopher Jeremy Bentham [9] to allow the staff to observe inmates at all times from a central location. Unlike the case of the one-way observation Bentham described, the Internet is much more complex, as the “inmates” observe each other, and even the Panopticon’s staff, as for example in Edward Snowden’s leaking of NSA documents or Julian Assange’s Wiki-Leaks site.

The erosion of privacy is further exacerbated by the many information aggregators who are engaged in deliberate collection and dissemination of information, some public and some gathered from semi-private sources. While much information is currently in text format, another explosion in the availability of information will happen when new search tools will allow users to search for faces or voices [10]. For example, much has been written about the privacy implications of the Google Street View, when the camera captures faces of people in particular geographic locations (for example, a person entering a sex shop). These concerns will be much more severe when it will be possible to use a digital photo of a person to search for that face in similar photos online, to uncover information that is linked to the photo (name, address, etc.). Some think such a technology is already available at Google, but is not being released because of privacy concerns. The most insidious aspect of the death of privacy is that privacy is no longer an individual choice. Photos about a privacy-conscious individual may be posted online by others in her social circle or even by strangers that unintentionally capture the user in their photo. One does not have any real choice in this respect, other than completely withdrawing from society. And even then, generic information about one’s gender or race will leak out as databases allow profiling for an entire demographic segment, even though not the entire demographic segment has consented to sharing that type of information (for example inferring disease proclivity from DNA data).

What can be Done?

As communications technologies appear likely to make privacy obsolete, several authors have suggested ways to preserve or replace privacy. Some extreme positions, like that of the former Sun Microsystems CEO Scott McNealy, claim that “(y)ou have zero privacy anyway. Get over it” [1]. Others, like Ann Cavoukian, Ph.D., Information and Privacy Commissioner of Ontario, call for technological solutions that can ensure privacy [11]. A third group agrees that technology cannot help contain information and suggests a focus on the legal remedies arising from the improper use of private information [12]. Finally, a fourth group views privacy as an ethical duty of the information recipient [8].

Sadly, none of those approaches provides a complete solution. Simply giving up on privacy is just not likely to happen; the death of privacy will require considerable changes and adjustment in society. As chief Google economist Hal Varian puts it, “privacy is a thing of the past. Technologically it is obsolete. However, there will be social norms and legal barriers that will dampen out the worst excesses” [13, p. 133]. Technological measures can protect privacy to some extent, but are useless to undo an information leak after the fact. Even if the probability of a leak is very small, over time much of the information that starts as private will no longer be private. Finally, legal protections make sense when dealing with reputable organizations under a common jurisdiction, but fail when dealing with people outside the law, or when law enforcement contracts with a private entity to carry out the data laundering [10, p. 213]. A Wall Street Journal article titled “Hackers-for-hire are easy to find” revealed that fees ($400 to access another person’s email account) are affordable even for private citizens [14].

In this article we deconstruct privacy and identify several privacy areas that will see different treatments. If privacy becomes unattainable, the outcome and societal impact will be different in each area. In that spirit, we view private information as falling into one of four categories:

- Private information about illegal activities.

- Private information about legal activities that are not generally acceptable in the society.

- Private information about legal activities that are relatively common, but not flattering.

- Private information that is used as personally identifying information.

Private information can be collected by either private citizens (or private organizations) or by governmental entities. The motives behind capturing information may be as diverse as state or corporate policies, blackmail, voyeuristic inclinations, vigilantism, or random chance (capturing private information unintentionally). Legal protections against capturing and using private information depend on both the nature of the collector and on the motives. Some legal protections of private information exist, for example requiring a warrant to conduct certain searches. On the other hand, if information will leak, the original place that leaked the private information may not be relevant. Once collected and made public, information will be available to all entities, with or without a search warrant. In the next sections, we explore what zero privacy means for each of the four categories of information listed above.

Illegal Activities

Some people think that if you are not doing anything wrong, you should not care about privacy. David Shipler [15] points out that this statement depends on what “wrong” means and who gets to define the term. After all, Lavrentiy Beria, head of Joseph Stalin’s secret police, is rumored to have said “Show me the man and I’ll find you the crime.” At least within the confines of the legal system, the definition of “wrong” includes activities that are in violation of current laws.

Many privacy laws have to do with restricting governments’ ability to invade citizens’ privacy. Still, legal limits to government data collection continue to dissolve and may disappear completely as more information is leaked out without government intervention. One threat to privacy arises from the increased use of surveillance cameras in public places. Video recordings from surveillance cameras have at times helped solve crimes [16], sometimes within only a few days [17]. The same surveillance cameras sometimes capture videos of police brutality [15]. Citizens with mobile phones capture videos of police brutality [18] and document overreaction of oppressive regimes, most recently during the Arab Spring uprisings [19]. Government law enforcement is subject to rules and regulations, but evidence seized by private citizens can be used by law enforcement with fewer restraints – which has led to partnerships between police and private law enforcement groups [15].

As long as customers are able to blog, comment, and take action online when they feel they are wronged, that check will be available to counter the power of merchants to bully consumers.

Although currently protected to some extent, private information about illegal activities will be the first to leak out, as it will be the target of both law enforcement and private citizens looking to blackmail the information owner, to collect a bounty, or simply to enjoy the thrill of uncovering information. The mere threat of leakage of information about illegal activities might lead to a reduction in illegal activities, as people realize that much of what they do is subject to others blogging about it, photographing or videotaping it, or simply uncovering it via data mining across various data sources.

As private information about illegal activities becomes public, there are two ways that society will respond. First, if information becomes public and perpetrators get convicted more readily (a big if, but worth considering), this is likely to reduce the incidence of certain illegal behaviors. On the other hand, if certain currently illegal behaviors prove to be common or if the punishment does not seem to fit the crime, it is likely that our laws will change to allow the activities to become legal. Ultimately, through the combination of these two means, it is likely that there will no longer be an expectation of privacy for illegal activities.

Legal Activities that are not Socially Acceptable

As the Internet is making the collection, distribution and use of information more available to anybody, privacy is steadily eroding.

As with information about illegal activities, the response to this type of information becoming publicly available is two-fold: people will either cease to engage in legal but socially unacceptable activities (unlikely) or the society will learn to accept more of what is legal. Many activities that are currently legal and acceptable were illegal earlier; they later became legal but frowned upon; finally, they are currently increasingly mainstream. For example, over the course of the 20th century, same sex couples have gone from being arrested for violating state laws, to being increasingly open about their relationship, to seeking legal recognition. The U.S. Supreme Court recognized same sex marriages in June 2015, by declaring individual state bans against same-sex marriages unconstitutional. As another example, many types of crimes against oneself or victimless crimes that used to be illegal are slowly becoming acceptable in the society (marijuana consumption, for example).

Private matters under this heading will evolve in one of the following three possible directions:

- Some private matters will be more readily shared because they become more socially acceptable (just as sexual orientation used to be private, yet it is now shared widely by many gay people “coming out of the closet” – this statement is about a trend, rather than a fait accompli, as indicated by the tragic suicide of Tyler Clementi after his roommate made his homosexual inclinations public).

- Some private matters will be more readily shared because of increased willingness to share. Many of the young adults nowadays have a different expectation of privacy. A Pew survey [1] found that people are much more willing to share private information and do not have an expectation of privacy in many areas that used to be private just a generation ago.

- Some private matters will still not be willingly shared – such activities and traits will tend to diminish and disappear because of the threat of their being disclosed anyway. Unlike with illegal activities, the pressure for disclosure of these activities and traits will be lower, but they still will be the object of prurient curiosity and malicious activities.

Legal Activities that are Acceptable, but “None of Your Business”

Many privacy concems relate to activities that are not illegal or immoral, that many people participate in, but in which people are not willing to publicly admit their participation. This type of information includes some of the places we visit, some of the things we say, and some of the data about ourselves (e.g., how much money we make and the state of our health). As such, these aspects of privacy have to do with information that is more or less public, but not widely available.

Much has been written about privacy in public spaces. For example, driving a vehicle on public roads is hardly a private activity, yet the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against police tracking the vehicle via a GPS device attached to the car without a warrant [21].

Sometimes the loss of privacy is by association. Posting information about one’s employment situation may be fine from that person’s point of view but might violate the privacy of her colleagues or her employer. More troubling, posting information about one’s genetics might impact blood relatives (both descendants and progenitors), but also members of entire racial or ethnic groups. For example, a father posting on a blog about his own genetic problems related to chromosome Y will in effect disclose the same problems for his sons who share the same chromosome Y.

Another aspect of the “none of your business” private matters is that context is important. A quote, a visit to a place, or a meeting could be taken out of context and made to seem something they are not. As private information leaks out, increased transparency will provide more context as well, which is likely to minimize fears of misinterpretation.

Much of what we view as private is culturally or socially specific: for example U.S. tax and income records are private, while in Norway and Finland they are in the public record; U.S. politicians are required to disclose tax information while Swiss politicians are not supposed to reveal theirs [8, p. 31]. What is private also changes over time. In the U.S., where salary information used to be a matter of secrecy, the compensation of an increasing number of professionals is now in the public domain, including public officials and key executives in publicly traded companies, and also compensation for government employees in general. With the proliferation of online databases, of mobile devices recording video and sound, of search capabilities that may include biometric based searches (gait recognition, face recognition, voice recognition, etc.), and with the ability to aggregate information across multiple data sources, it is likely that information about pretty much anything we do will become public. Whether anybody will care about searching for us may be a different issue, but the capability will exist. Any expectation of privacy of the “none-of-your business” type will be greatly reduced or eliminated.

Legally Protected Private and Personally Identifiable Information

A final and most troubling type of private information is information that can identify its owner. Currently, personal identities are defined by a few key data pieces that are supposed to remain private (social security number, date of birth, mother’s maiden name, for financial records; a password sometimes combined with another form of authentication for computer authentication). If these data are leaked, an individual’s identity can be stolen and she can incur financial damages, as well as damages to her reputation. A password can be changed if it was compromised, but any unauthorized access with a valid password will be indistinguishable from an authorized access with the same password. Identity theft is much more difficult to undo, not only because of the major economic implications, but also because it is based on private information that cannot be changed if compromised.

The problem here arises from relying on privacy to ensure information security. While none of the information about individuals can be protected well enough to guarantee security, researchers are working on developing new ways to identify people without relying on private information. Much of these new ways are based on biometrics, traits intimately related to human bodies, and that are unique enough to confirm the identity of their bearer. To avoid risks associated with a lost biometric (which cannot be replaced) research has focused on biometrics that cannot be duplicated or stolen. These new-generation biometrics include keystroke dynamics [22], mouse dynamics [23], eye gaze dynamics [24], etc. If we accept the premise that any private data can and will be leaked out, these biometrics appear to be the only way we could identify people securely, decoupling security from privacy.

A Life Without Privacy

As privacy continues to be eroded and may even disappear, humankind will end up living in the virtual equivalent of a “small” village.

We started with the premise that any private information may eventually become public, and we considered how society will cope with this transformation. Many privacy concerns are already addressed in the law. For example, in some countries it is illegal to discriminate based on sexual orientation. It is generally also illegal to blackmail someone, whether about legal or illegal activities. As existing laws clash with the erosion of privacy and the wider availability of private information, laws will need to change to accommodate the availability of information that was previously prohibited.

Demographic Information in Employment and Healthcare Decisions

Current laws prevent employers from obtaining certain types of information about employees, including some types of health information, demographic information about prospective applicants, or location information (tracking employees outside of the scope of employment). For example, an employee who visits an alcohol addiction clinic or a fertility clinic might disclose health related information to her employer if her location is tracked [25]. While many legal protections currently limit the acquisition of information, it is likely that in the future employers will be held accountable for how public information about their employees is used. It will be difficult to prevent an employer from having access to health and demographic information about employees and applicants once this information is public, but information about the decision making process at the employer level also will be available, possibly via employee blogs, whistleblower discussion boards, or similar forums. While keeping certain types of information private may not be possible, the employer might be prevented from using such information to discriminate against employees or applicants in cases where the law requires non-discrimination.

While the use of some private information may continue to be protected by laws, the law might also evolve to explicitly allow the use of some of the private information. For example, as part of the increased availability of all types of information, there likely will be an increase in the incidence of statistical discrimination. The practice of treating demographic groups differently based on sound statistical differences is already legally accepted in insurance, where lower-risk groups pay lower rates (non-smokers are lower risk than smokers, married men are lower risk than unmarried men, younger people are lower risk than older people, and women are lower risk than men). As more information becomes available, the features available for statistical discrimination will become more numerous, and their use is likely to become just as acceptable as the current use of demographics.

Purchasing Habits and Advertising

A whole category of private information concerns people’s purchasing habits. Organizations track purchasing habits online via ecommerce websites. and offline via loyalty cards, and then use this information in their marketing activities. Many people are concerned about the privacy implications of this information collection. One example is the case of a sixteen year old girl, who was sent pregnancy related promotions by Target. Her father called to complain, but soon after found out that the girl was indeed pregnant, and that the Target data mining algorithms were able to infer the girl’s state from her shopping habits. To avoid spooking customers, Target later chose to disguise its marketing capabilities, by mixing targeted and random offers, but the capability to uncover and exploit customer needs will only increase. In addition to the creepy feeling that the merchants know too much, consumers are also concerned with errors in the information collected, as well as with a barrage of unsolicited and unwanted advertisements.

The death of privacy gives three reasons of hope for consumers. First, companies that collect the information will benefit only when the information collected is accurate, because errors will directly affect the bottom line, and might even lead to a competitive disadvantage for the merchant relying on erroneous data. The second reason for hope is that companies have an interest in keeping customers happy, especially when customers’ voices can resonate in online forums. As long as customers are able to blog, comment, and take action online when they feel they are wronged, that check will be available to counter the power of merchants to bully consumers. There are numerous examples of organizations that have had to reverse policy decisions in response to customer complaints, because of the force of online social media (e.g., Facebook and Netflix). Some argue that, to keep customers happy, companies should give customers opt in choices as opposed to opt out choices or no choices at all. Opt-in practices are not required in current legislation. In particular, companies are free to collect transactional data for operational reasons, and any limitations are only on sharing this data with certain third parties.

A third and final reason for hope is that accurate purchasing profiles may ultimately benefit the consumer. Companies will increasingly use targeted offers based on customer profiles, rather than the more traditional broad barrage of advertising. In the old days of small communities, an owner or sales clerk in a local store had knowledge to make relevant offers of new products, and they had consumers’ trust, encouraging buyers to try the items. As organizations continue to refine customer profiles, and as customer relationship management systems are able to better personalize offers to each customer, customers might receive fewer but more relevant offers, and might appreciate these offers more than generic unsolicited junk mail. This may sound like too much marketing optimism, but it is already happening to some extent. Netflix makes recommendations that customers trust and are glad to receive. Amazon reviews are an important component of the company’s success. As trust and openness in dealing with customers becomes a source of competitive advantage, companies will increasingly strive to involve customers, gain their trust, and effectively address their needs.

Peer Pressure, Blackmail, and Socially Unacceptable Behaviors

One other benefit of a society without privacy will be a simpler life. Conventional wisdom is that lying is more difficult than telling the truth because the storyteller needs to keep their story straight. If all information may be publicly available, even white lies will be more difficult, if not impossible. Even blackmail may cease to exist as a threat, because it relies on the assumption that information can be kept secret.

Privacy Steadily Eroding

As the Internet is making the collection, distribution and use of information more available to anybody, privacy is steadily eroding. Conceivably, the day will come when anybody will be able to find out anything about anyone else on the Internet. Before that day, society must solve two problems, one technological and one social.

First, on the technology side, we need to devise ways to uniquely identify individuals for purposes of closing legal transactions (financial, employment, voting, etc.). This needs to be accomplished so that the identity of an individual is protected and cannot be stolen, even if all information about that individual can be found online. Using social security numbers, birthday numbers, and mother’s maiden names will be increasingly risky, as will “security questions” like “What was your first dog’s name?” This type of information will be widely available online and will be easily searchable, making it unsuitable for any security application. Instead, future authentication schemes will have to be based on information that cannot be duplicated or stolen (e.g., a combination of biometric traits).

The second problem to be solved, which is a societal challenge, will be to put in place social and legal protections against all the other information leaks that are to be expected. As in the small villages of the past, individuals will have to either a) conform to the norms of the society, b) work hard to hide their lack of conformity (unlikely), or c) influence society to change and accept wider norms. With this expectation, most actions an individual will take will be reflective of the socially accepted standards, whatever they are. This might result in a fragmentation of society into smaller groups of like-minded individuals, united by common values and interests, with people living according to their group identity. There were always different expectations and different behaviors for citizens in a small village and for pirates in their safe harbor.

Some people love the small village life, and some people hate it, but as privacy continues to be eroded and may even disappear, humankind will end up living in the virtual equivalent of a “small” village – where everybody knows, or can know everything about everybody else – and where the village comprises the entire world.

Author

Bogdan Hoanca is Professor of Management Systems, University of Alaska Anchorage, College of Business and Public Policy, 3211 Providence Drive, Anchorage, AK 99508. Email: afbh@cbpp.uaa.alaska.edu.

Bogdan Hoanca

JOIN SSIT

JOIN SSIT